It’s interesting that even though Volvo was behind one of the very first concept cars, the Venus Bilo, it’s a company which until the 1980s focused almost exclusively on creating production cars. And even when Volvo did build a concept in the 1980s or beyond, it was generally an early view of a production model or it was a test bed for a new bunch of safety technologies such as a new restraint system or a new type of crash structure.

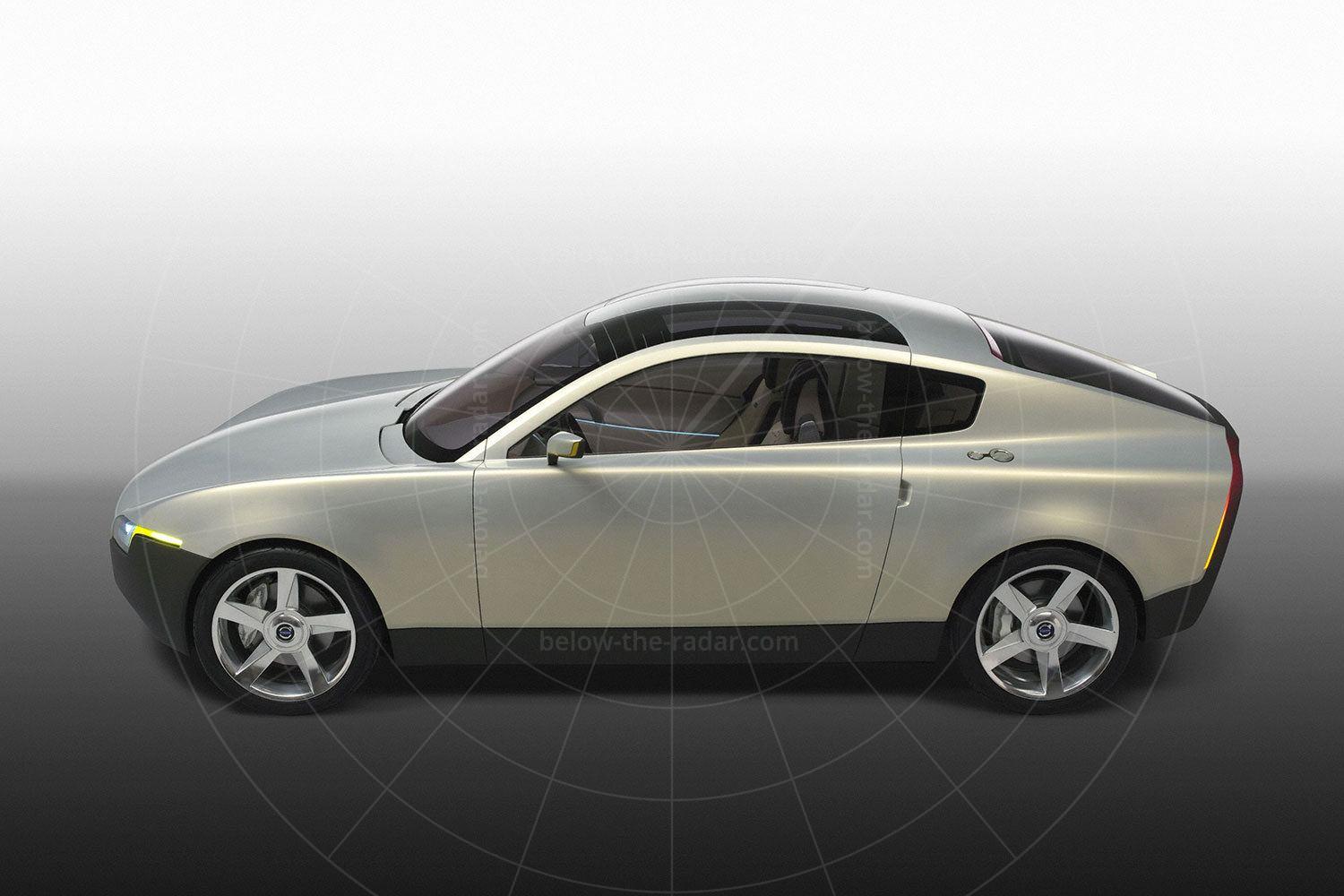

For example, the ECC of 1992 was effectively an early view of the original S60 and S80, while the VCC was a preview of the 700-Series that would appear in 1982. Indeed, take a look at just about any concept to come from Volvo and it’s been followed at some stage by a production model that looks largely similar. But there has been a notable exception to this rule and that’s the YCC, or the rather awkwardly named Your Concept Car.

The idea behind the YCC cropped up in 2001, when Marti Barletta paid a visit to Volvo. An American expert on female consumer patterns, Barletta suggested that Volvo put together an all-female team to come up with a car that would meet the needs and expectations of women. Intriguingly, her argument went that if they could do this, any male potential customers would be happy as they’re far less demanding than their female counterparts.

By the summer of 2002 the all-women team had been assembled; their task was to create the perfect car for the modern, independent professional woman. By this stage more than half of Volvo’s US buyers were women, and Volvo’s research suggested that women buyers in the premium segment were the most demanding consumers of all; if the company could keep them happy, it could keep anyone happy.

Long before it became fashionable, Volvo adopted a green ethic. As a result, its cars were among the greenest available, even though they had a reputation for being built like tanks with a thirst to suit. So when it came to working out what mechanicals to fit to the YCC, it wasn’t a difficult choice to make; it would fit the five-cylinder PZEV (Partial Zero Emissions Vehicle) petrol unit that was already capable of meeting the world’s most stringent emissions regulations – those of California.

Capable of generating a handy 215bhp, this 2.5-litre unit featured what was then termed ISG, or Integrated Starter-Generator. Since then the technology has generally become known as stop/start or Intelligent Stop and Go (so still ISG). The idea of the technology was that it would switch the engine off when the car came to a halt and when the accelerator was pressed it would automatically set the engine running again.

The engine drove the front wheels via a six-speed semi-automatic gearbox, which meant that the driver could choose the gears manually or could leave the car to do everything, the idea being that in the latter mode the car would be even more frugal thanks to its computer selecting the optimum change-up or change-down points. Those gears were selected through using paddle shifts on either side of the steering wheel – a feature that would become increasingly popular in time, but which was still a rare fitment when the YCC was unveiled.

Also, in a bid to cut fuel consumption at speed, there was height-adjustable suspension. The YCC would lower itself automatically when travelling quickly, but when driving more slowly the car’s ride height could be raised, to negotiate speed bumps or other hazards.

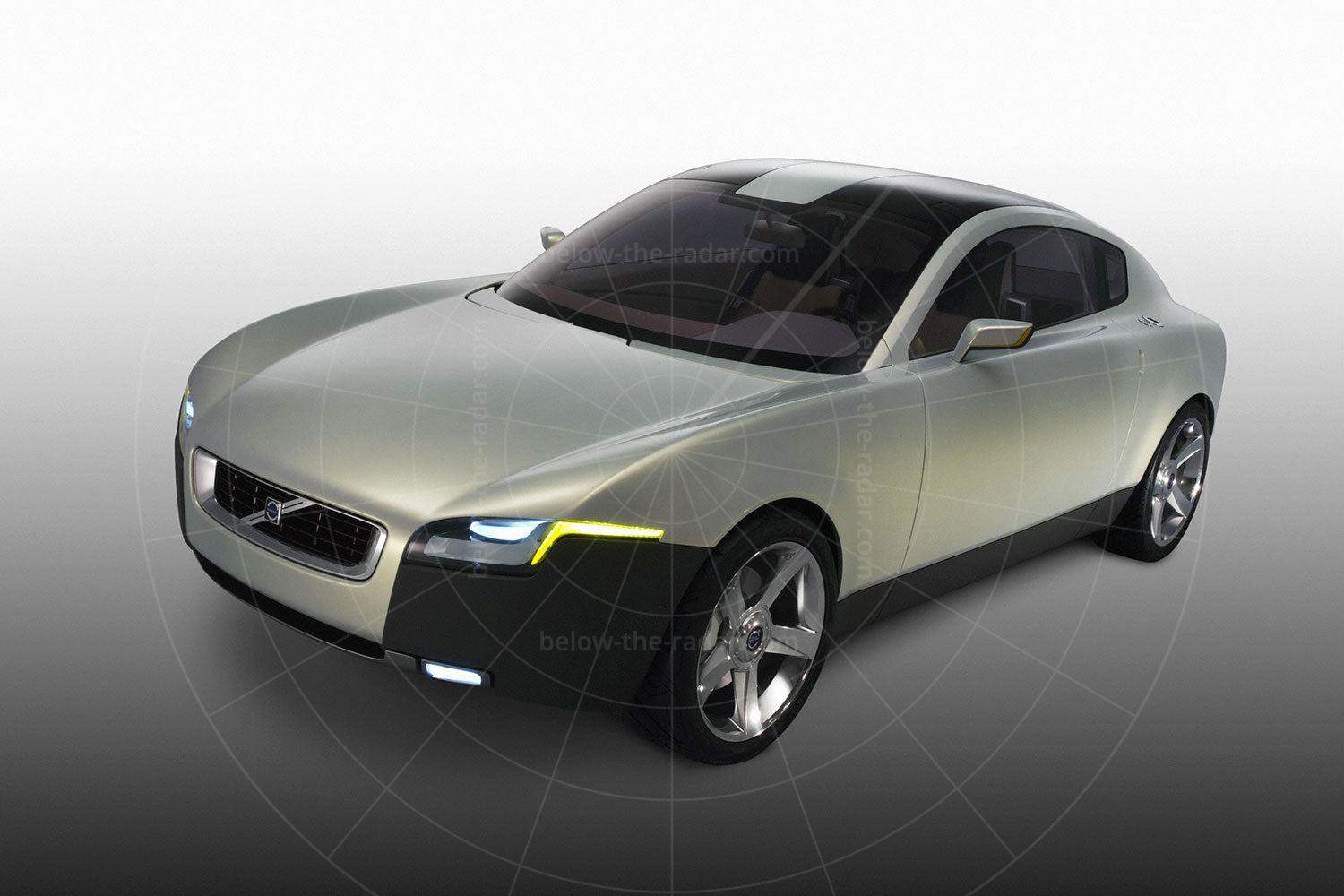

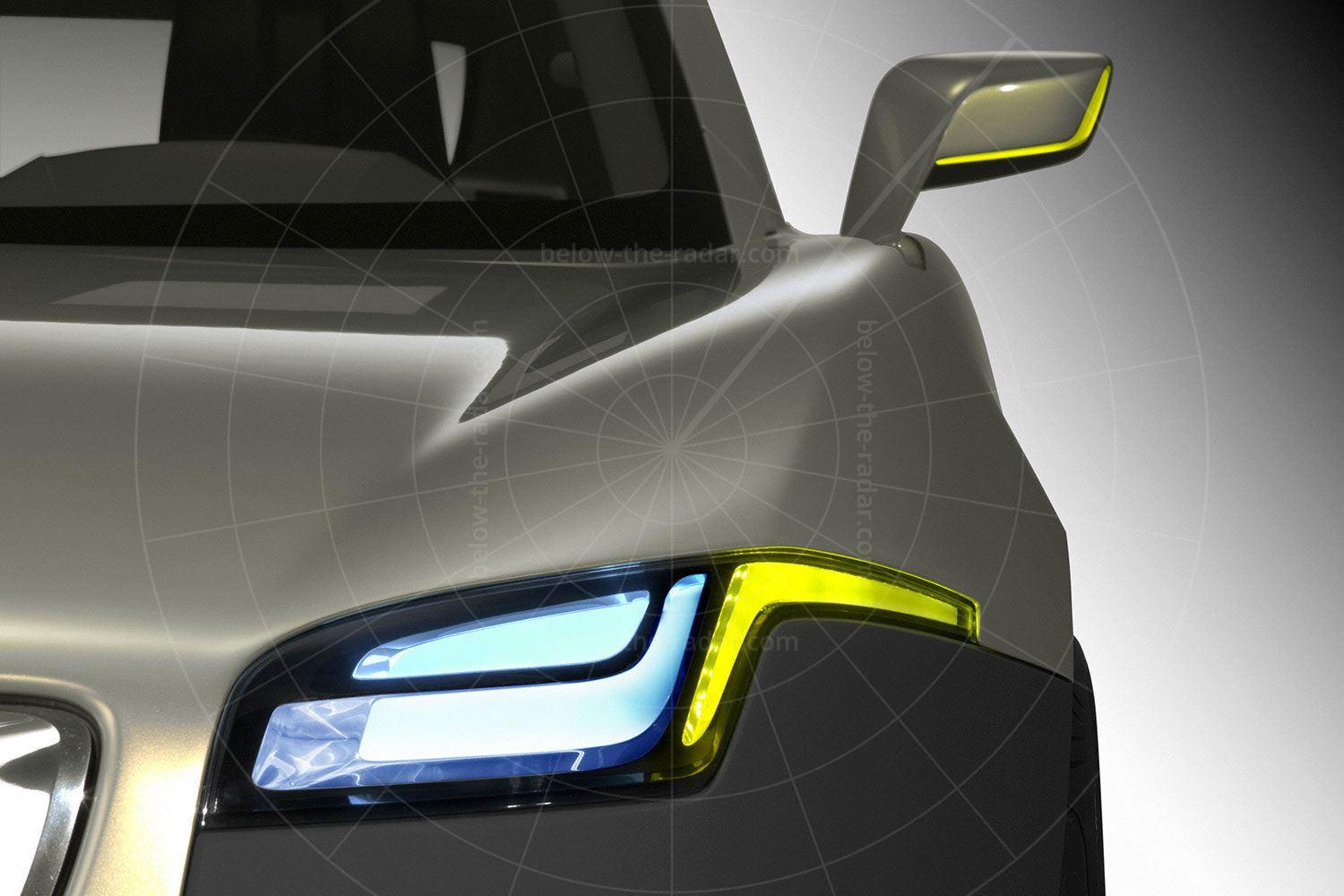

Of course a neat design inside and out was essential for the YCC, but as you’d expect, the designers’ brief was much wider than that. Particular attention had to be paid to things like storage, usability and access. Easy parking, personalisation opportunities and good visibility were important too.

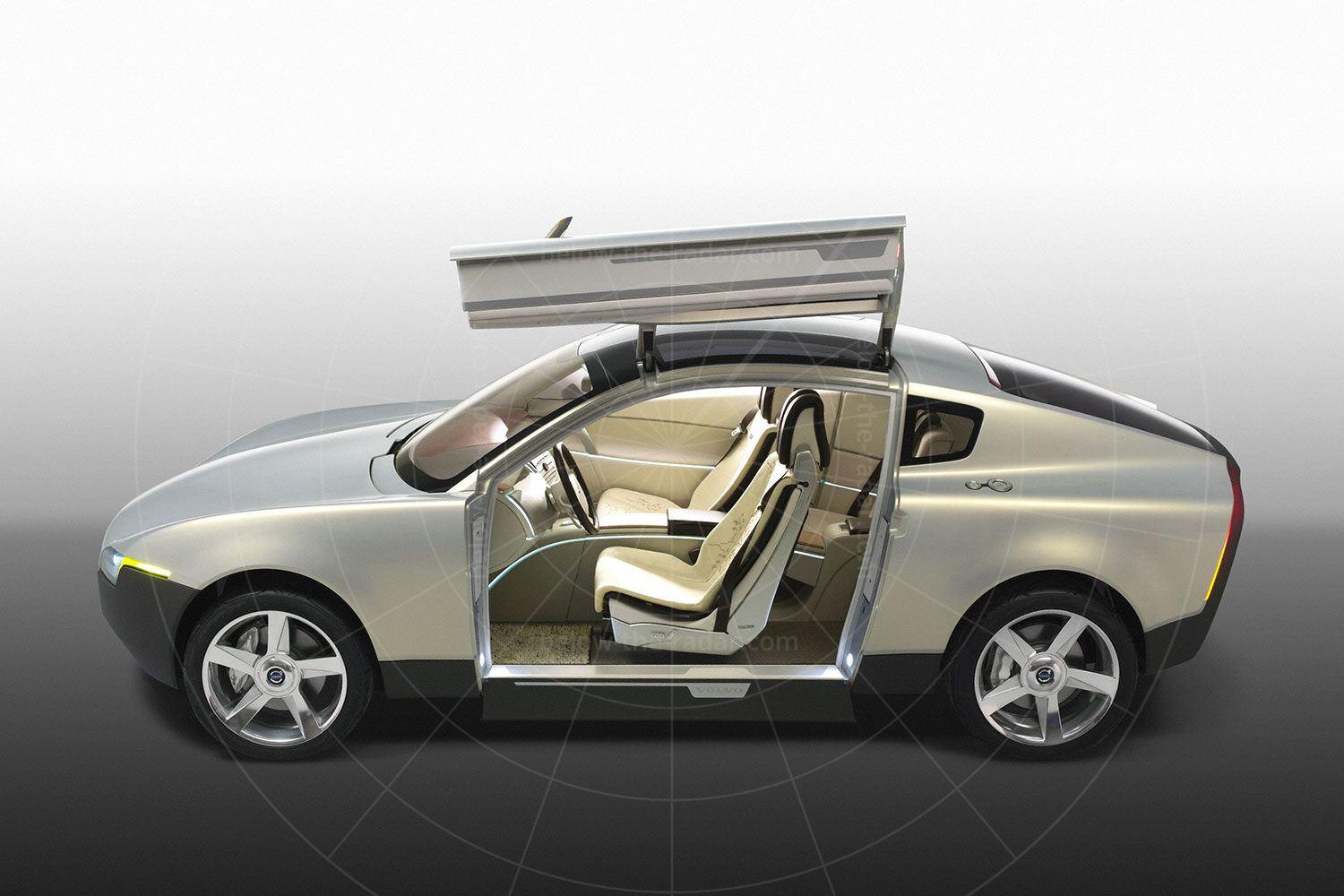

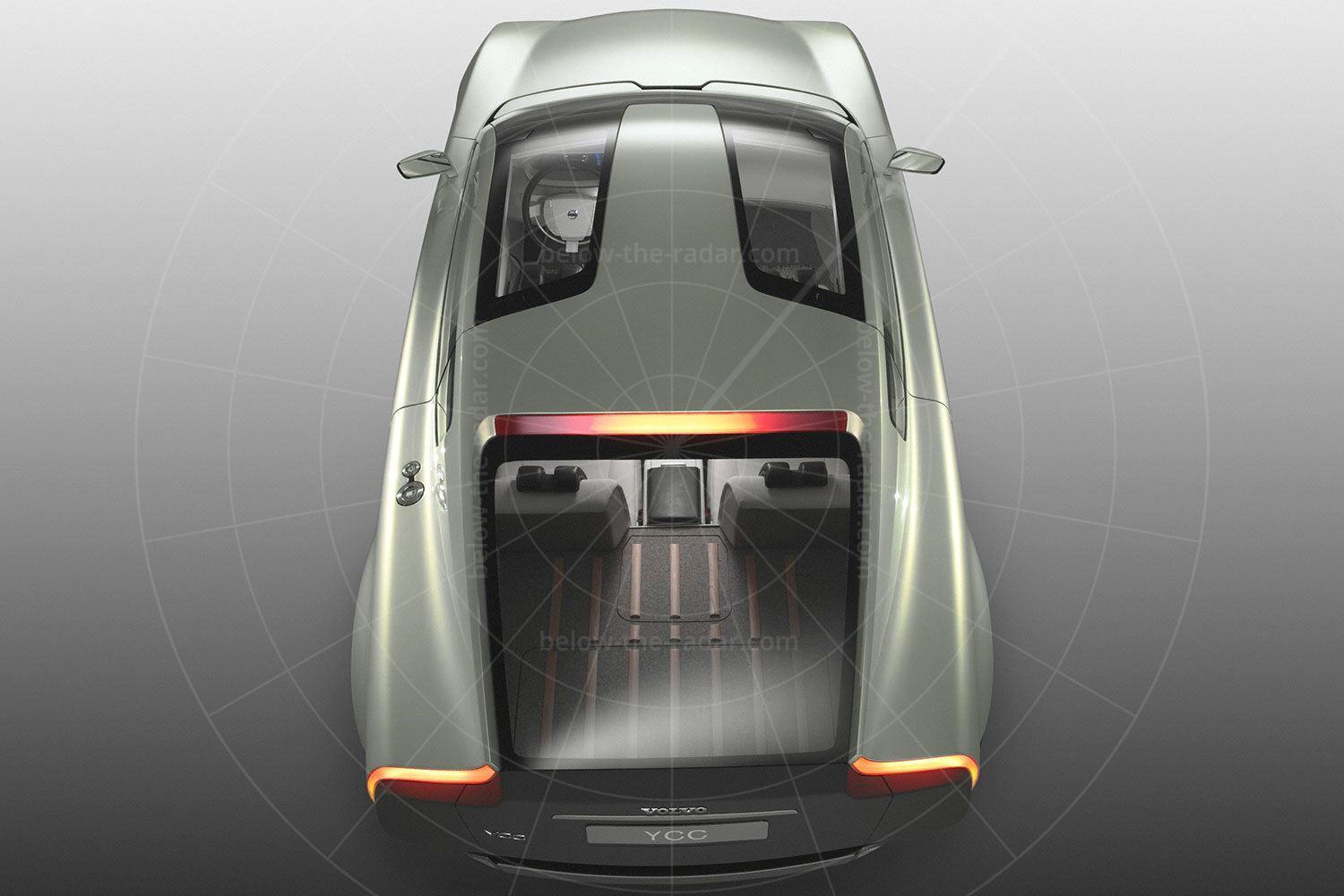

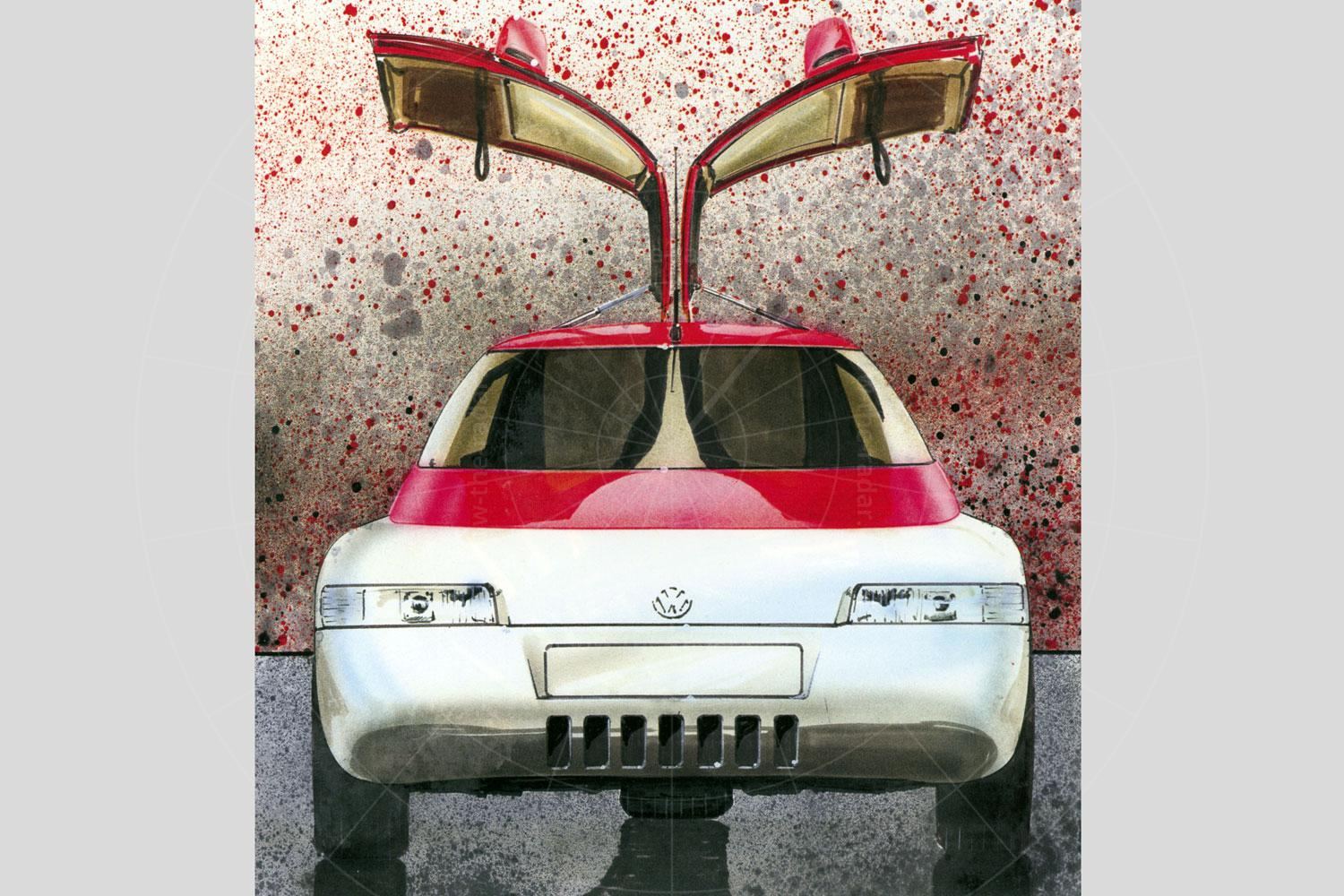

Taking all of these things into account, it was reckoned that gull-wing doors would provide the best method of getting in and out. Naturally there was power assistance, but in an especially neat twist the car would detect when you’d moved alongside it and the door would automatically open for you. So if you had your hands full, you wouldn’t have to put everything down then wrestle with the mechanism.

Ease of parking was taken into account with a park assist programme which would self-park the car thanks to a series of sensors. But it was visibility that was at the fore of much of the interior and exterior design; the driving position and line of vision are crucial for safety and comfort. So when ordering your YCC your whole body would be scanned at the dealership, then the data on your relative proportions (height, leg length, arm length) would be used to define a driving position just for you.

This information would be stored in digital form on your personal key, and once you climbed into the driver’s seat and docked your key in the centre console, the seat, steering wheel, pedals, head restraint and seat belt would all be adjusted automatically.

| Vital statistics | |

|---|---|

| Debut | Geneva 2004 |

| Design director | Maria Widell Christiansen |

| Exterior designer | Anna Rosén |

| Interior designer | Cynthia Charwick |

| Engine | Front-mounted, 2521cc petrol, 5-cylinder |

| Transmission | 6-speed semi-auto, front-wheel drive |

| Power | 215bhp |