In 1971 if you wanted a car that was seriously expensive and exclusive, it wasn't a Rolls-Royce, Cadillac or Ferrari that you bought. Instead it was a Stutz Blackhawk, fresh on the scene as part of a brand revival that had nothing to do with the original Stutz of the pre-war era, which had gone bust in 1937 as a result of the Great Depression.

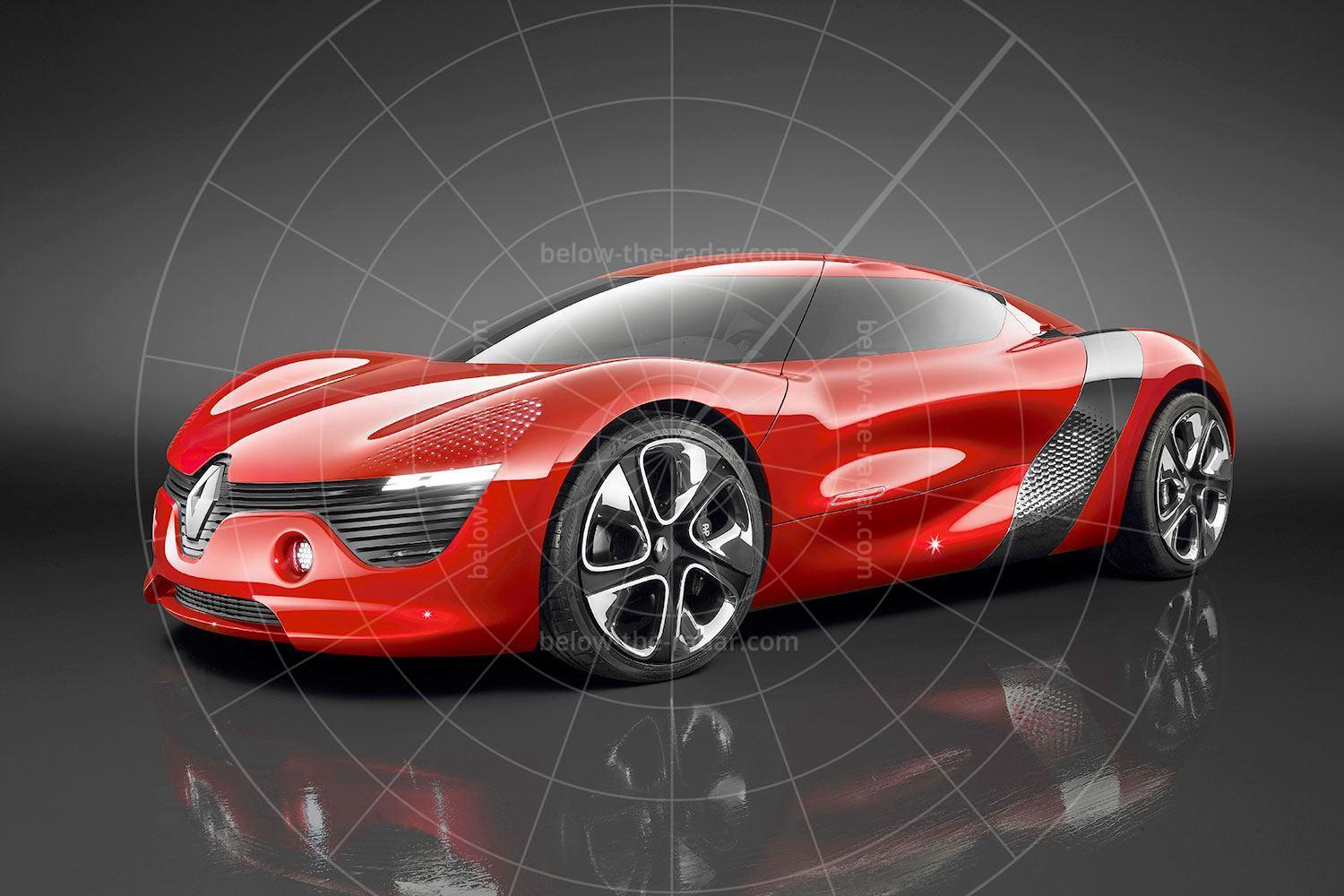

During his tenure as the head of Chrysler design, Virgil Exner defined the iconic fins-and-chrome era of the 1950s with his revolutionary 'Forward Look' design language. Prior to that he transformed Chrysler’s stodgy image and introduced American buyers to sophisticated Italian style with the collaborative dream cars created alongside Gigi Segre of Carrozzeria Ghia.

Following an acrimonious departure from Chrysler in 1962, Exner served as a consultant and worked on personal projects. In the mid-1960s Exner designed a series of so-called 'Revival Cars' which were his interpretations of defunct classic-era models including Mercer, Duesenberg, Bugatti, Pierce-Arrow, Packard, and Stutz.

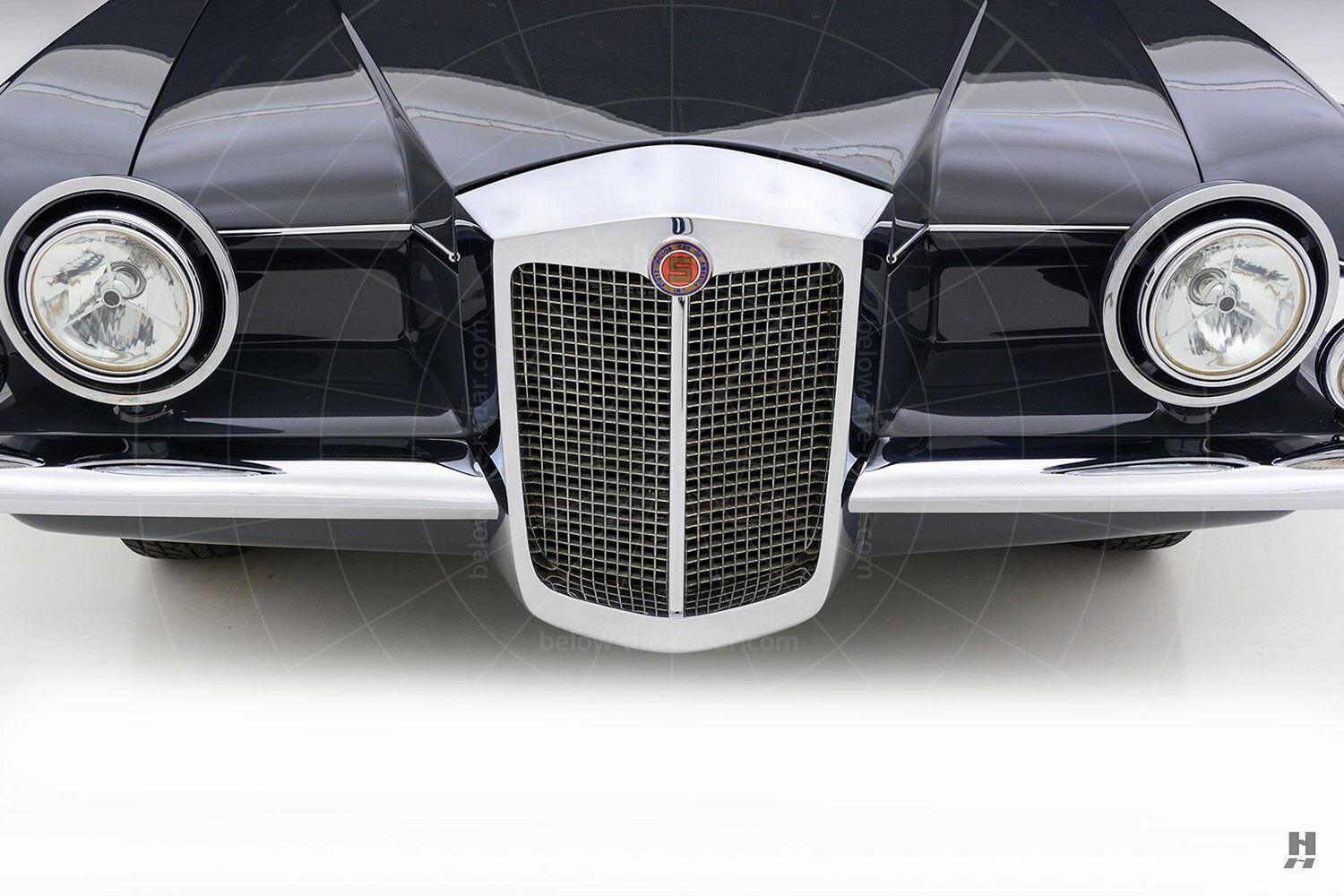

Exner tried and failed to revive Duesenberg, but in 1968 he turned his sights to a rebirth of the Stutz Motor Car Company. Financial assistance came from James O’Donnell, a wealthy investor with a particular fondness for Stutz cars and a talent for attracting investors. With O’Donnell in charge of the finances Exner had a free reign on the design, and soon a car worthy of the Stutz name took form.

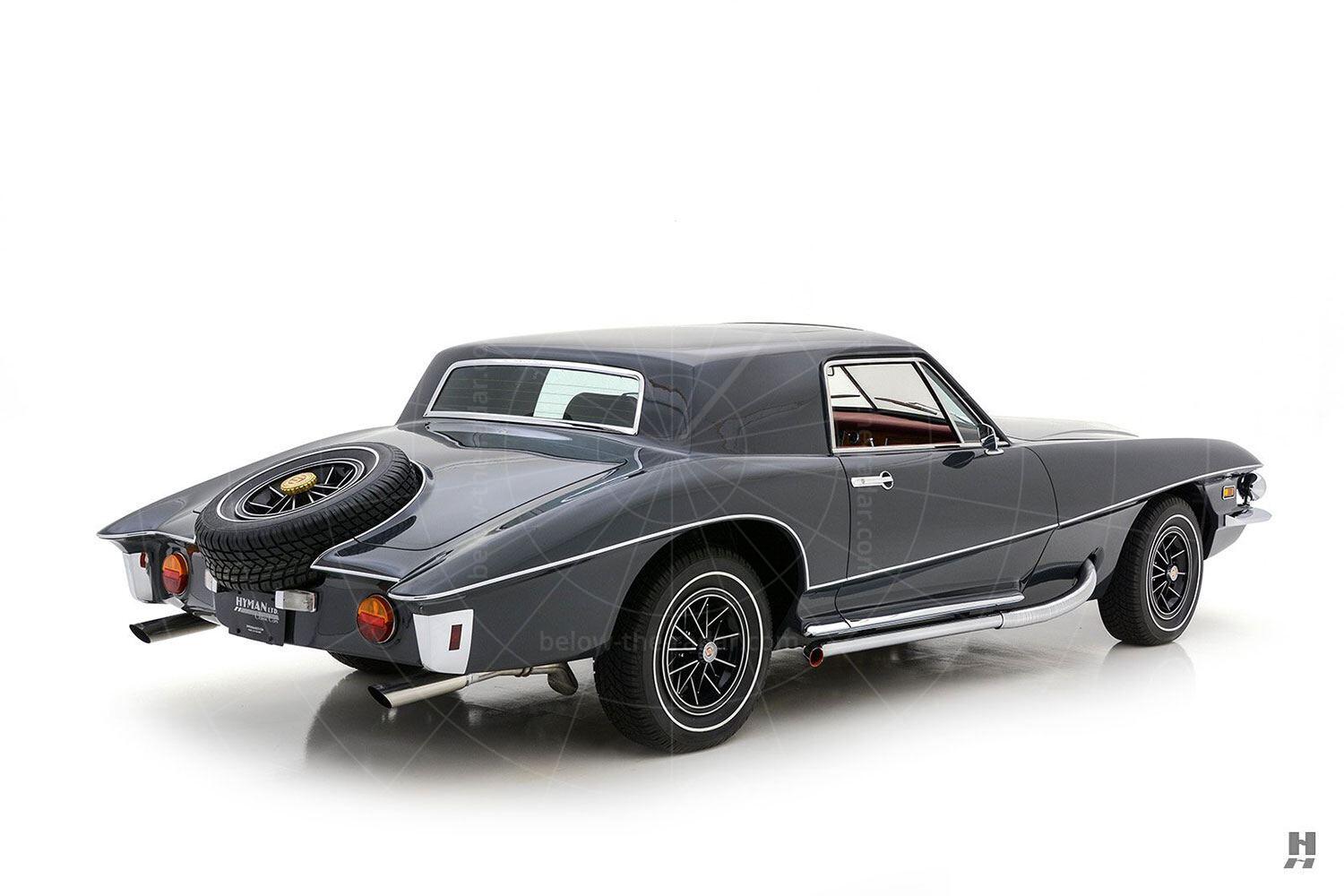

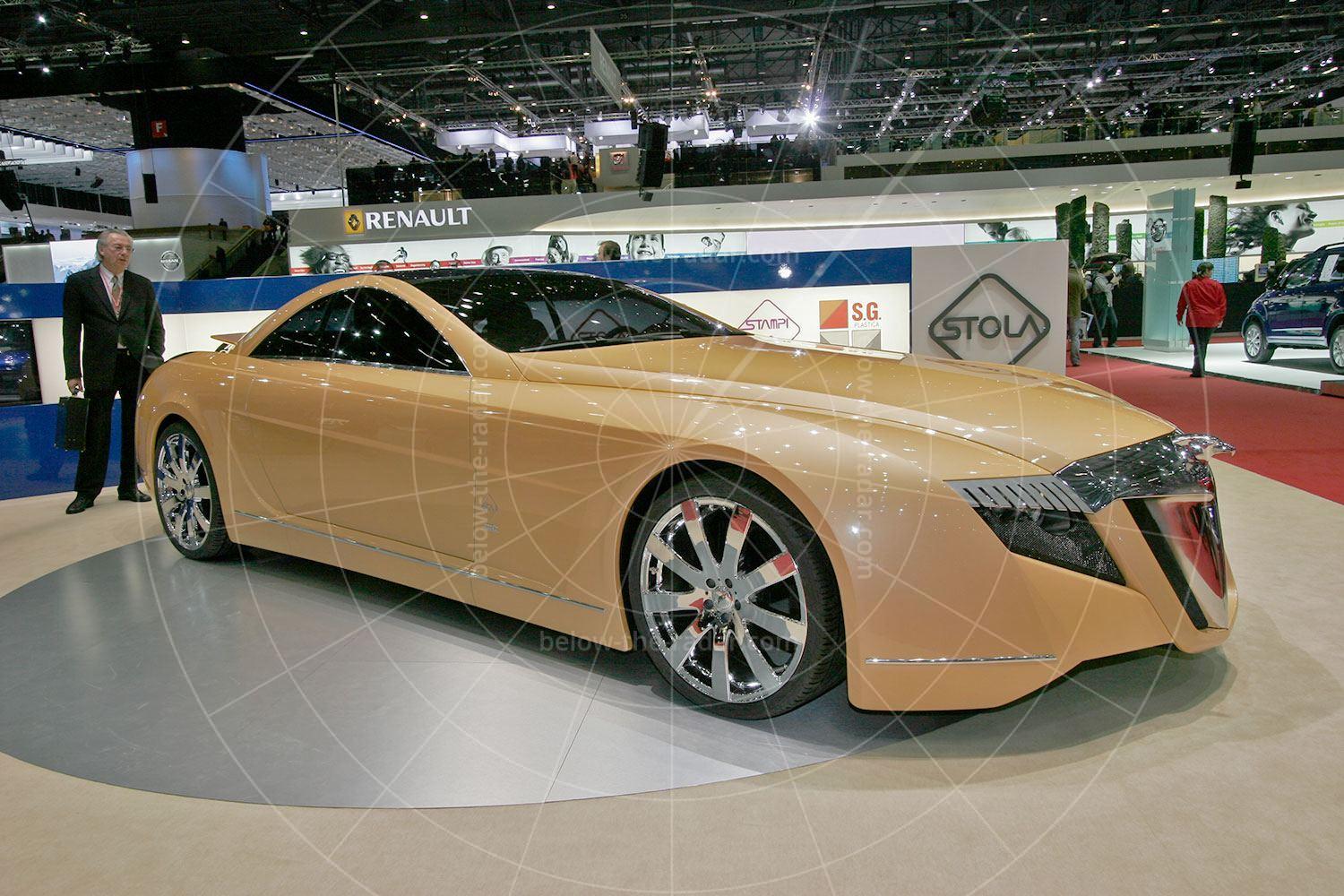

Virgil Exner’s vision of the Stutz Blackhawk was realised as an eye-catching, high-performance grand touring coupé, using American-sourced components in an exclusive, coachbuilt Italian suit. In the spirit of the luxurious and exclusive Dual-Ghia of the 1950s, the original Blackhawk was a fully engineered hand-built car, not a kit or glassfibre replica.

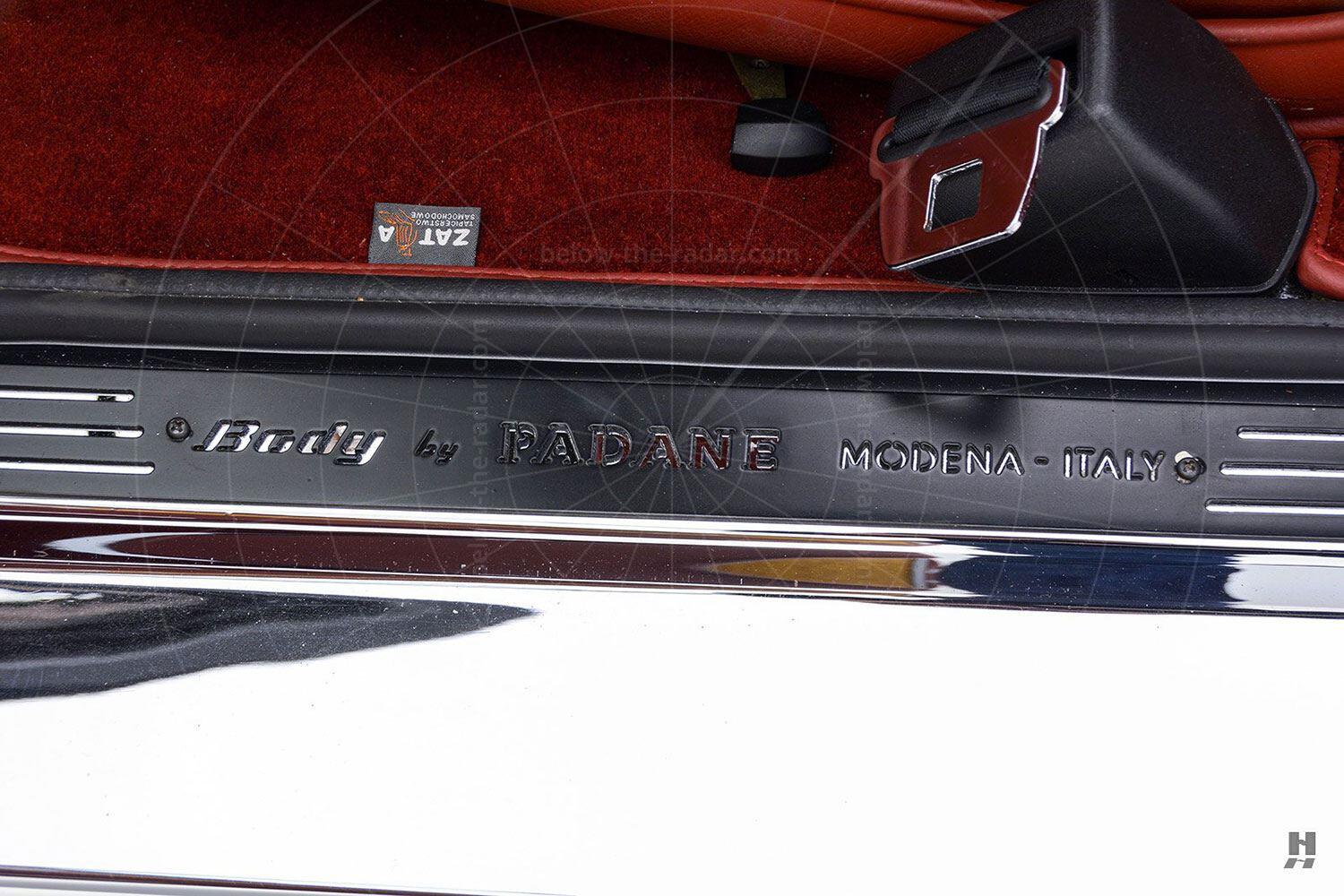

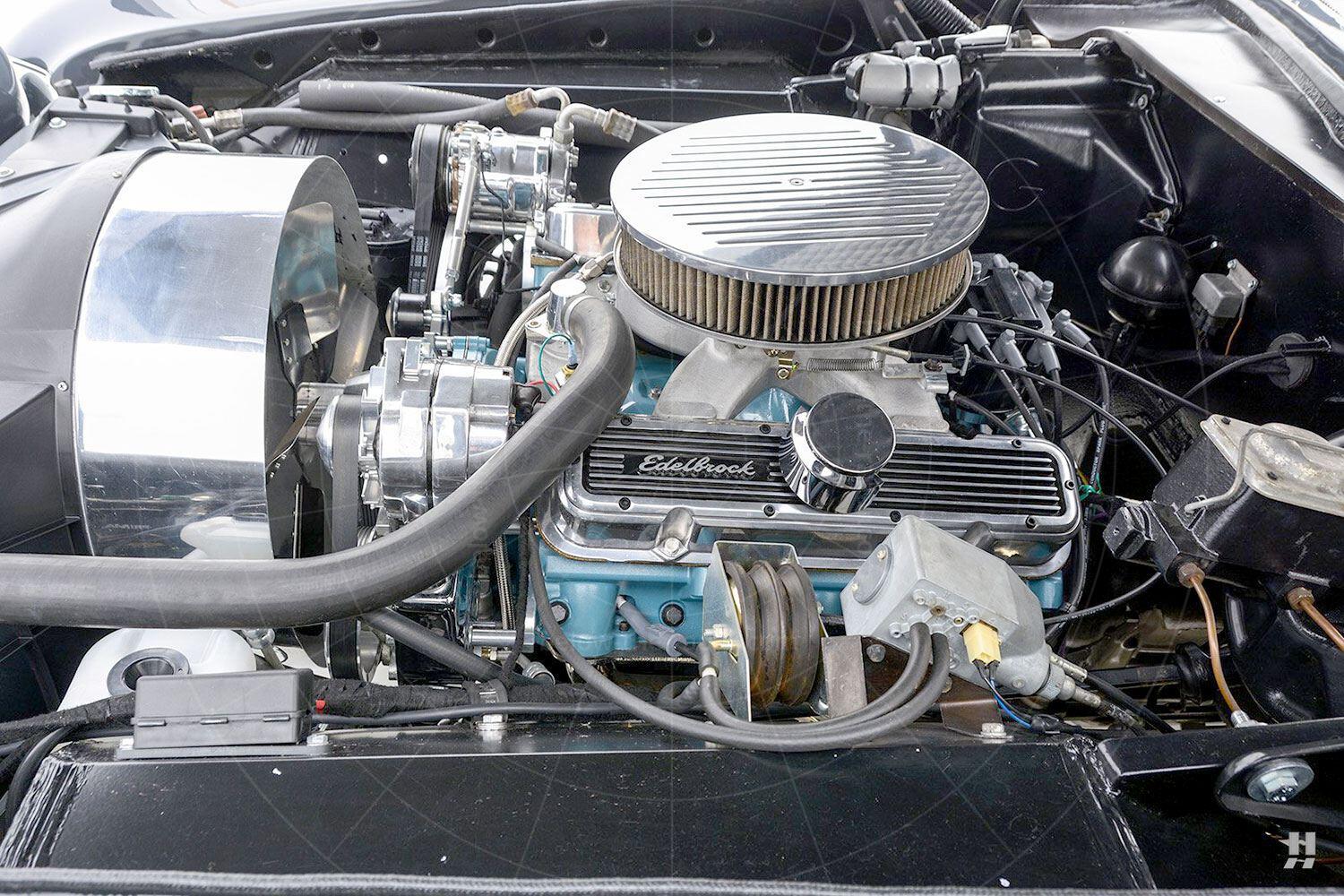

The costly production process involved shipping a complete Pontiac Grand Prix (purchased at retail) to Carrozzeria Padane in Modena, which discarded the entire body and interior. The new coachwork shared nothing with the donor car, and each completed bodyshell got high-quality paint along with luxurious leather and wood trimmings to the buyer’s specification. Those buyers included Dean Martin, Sammy Davis Jr., Lucille Ball, and most famously Elvis Presley, who purchased the first Blackhawk at its debut at the Waldorf Astoria hotel in New York; this example is now on permanent display in Graceland.

The studio-shot images here show one of only 25 of the distinct split-windscreen Series 1 Blackhawks that were built in 1971, carrying an eye-watering $35,000 price tag. That's the equivalent of nearly $225,000 in 2021, yet despite the exorbitant price Stutz lost around $10,000 per car before O’Donnell worked out that shipping complete Pontiacs to Italy only to throw much of them away wasn’t the best business plan.

From 1972 all Blackhawks used much more of the donor car’s substructure, compromising the unique proportions of Exner’s original design, but finally becoming profitable. But it is the early, coachbuilt cars that command the most attention from serious collectors, with just 16 of the original 25 Blackhawks thought to survive.

Initially only two-door coupés were officially available, but even at the outset Stutz was happy to build a four-door saloon if the buyer was wealthy enough. To that end Exner came up with the Duplex Sedan, in which the original Blackhawk design was extended and placed on a Cadillac chassis. It's thought that only two of these four-door Blackhawks were produced, of which only one had a body constructed by Padane and that car is pictured in the gallery here.

In the early 1970s (the Stutz timeline isn't at all well documented) a convertible was introduced which came in Bearcat and D'Italia flavours. Like all Blackhawks the production costs were insane, with parts borrowed from the Maserati and Ferrari parts bins, while the radio was the world's most expensive as it was produced by Lear for its jet aircraft. There was lashings of wood and leather, 24 carat gold plating and 17-inch alloy wheels; claimed to be the first ever fitted to a production car.

If you had really deep pockets Stutz was happy to build a stretch limousine for you, priced from $200,000 without extras. In the case of King Khaled of Saudi Arabia, one of those extras was a throne which rose hydraulically through the roof, so that he could better survey his subjects as he was driven past. The Shah of Iran also had a stretch limo but nobody knows how many of these most grandiose of all the Blackhawks were made. In 1979 Roger Cook drove a Blackhawk stretch limo for Car magazine, and didn't seem to know what to make of it:

The bowl of porridge ride around one of LA's tortuous freeway interchanges brought on a bout of genuine sea sickness for me. You couldn't call it car sickness because it was induced by a motion exactly like that of an overloaded dinghy in a swell. Anyway, it isn't a car to drive; it's a car to park - if you can manage it. So you park it strategically almost anywhere in Beverley Hills and bask in the warm glow reflected by all that chrome.

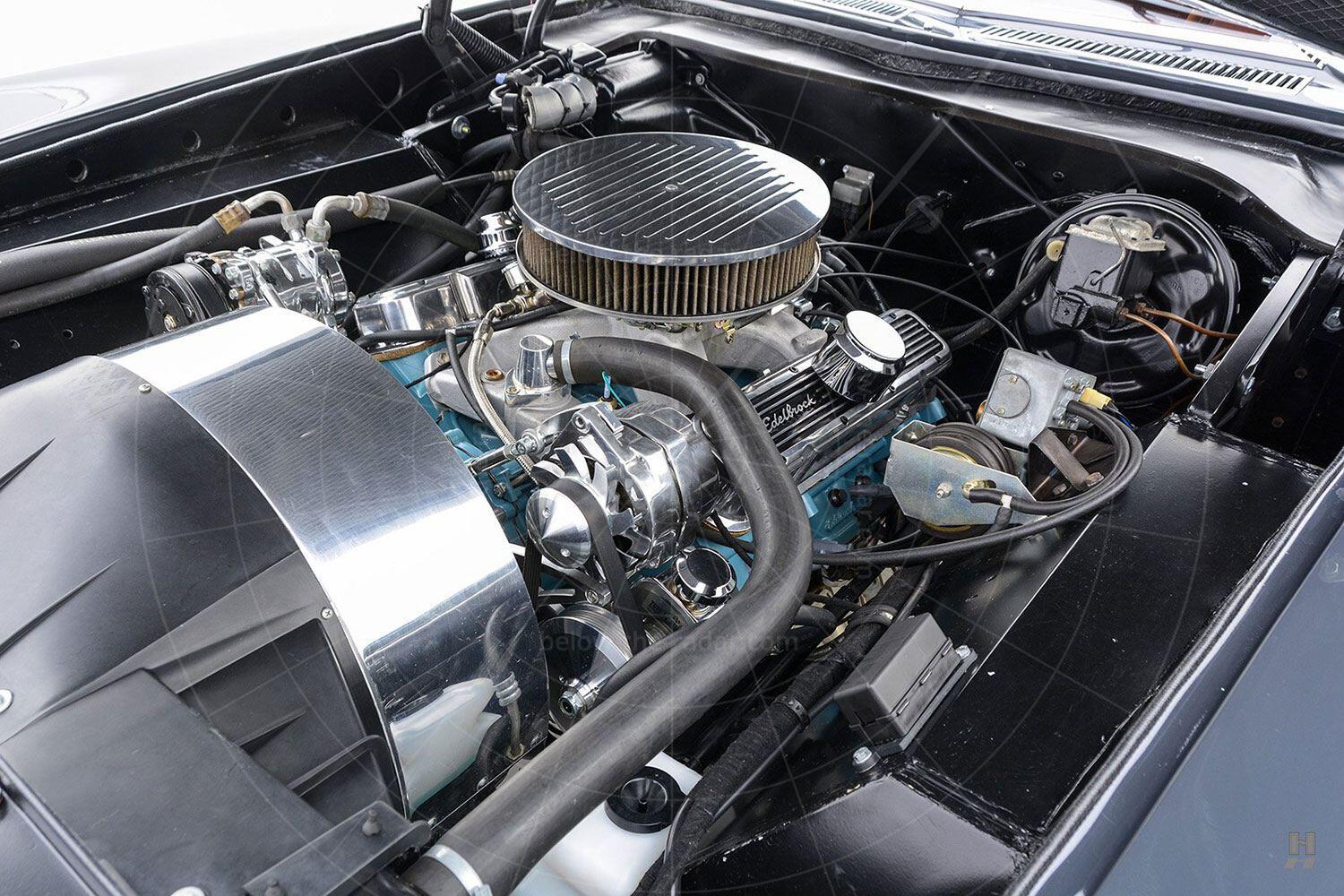

Not actually driving the thing does of course save petrol as well. Clad as it is in 18-gauge steel, a Stutz is no lightweight and even 425CID of GM V8 doesn't push it very far very fast.

To be fair, if you're happy to waste (er, spend) so much on the car in the first place, you won't mind wasting petrol too. For, most of all, this is a grossly wasteful car. Wasteful of energy, of resources and of craftsmanship. It is beautifully made, but why? Teams of Torinese coachbuilders labour long and lovingly to produce an automotive aberration of gargantuan proportions.

They labour six weeks over the 22 coats of lacquer, they hand rub the burr walnut, they hand burnish the gold fittings, they hand stitch the English leather and hand trim the exotic furs. Again, why? These artists could be building Ferrari rivals if someone gave them a sane design. The original Mr Stutz, who built genuinely stylish cars in the '20s, must be doing several hundred rpm in his grave.

Still, as I got out of the thing for the last time and turned to face its glittering lear and its flabby jowls, I had to admit to a not unpleasant feeling that I'd been for a short time party to a very expensive practical joke. It was so overwhelmingly awful it was actually fun! But how long you might retain that feeling should you have to spend rather more time with a Stutz is entirely another matter.

Stutz Blackhawk production lasted all the way through until 1987, by which time about 600 coupés, convertibles and saloons/limousines had been made. In those 16 years there were numerous fresh iterations of this most bizarre of cars; in 1980 the Pontiac Bonneville chassis was adopted and just five years later this was switched to an Oldsmobile Delta 88/Buick Le Sabre platform. As a result an array of engines and transmissions were fitted throughout the production run, all of them V8s, but some were supplied by General Motors and some by Ford.

| Vital statistics | Most stats are for the earliest cars |

|---|---|

| Produced | 1971-1987, USA |

| Number built | 600 approx |

| Engine | Front-mounted, 7456cc, V8 |

| Transmission | 3-speed auto, rear-wheel drive |

| Power | 431bhp |

| Top speed | 130mph approx |

| 0-60mph | 8.4 seconds |

| Price | $22,500-$75,000 (at launch) |

- Many thanks to Hyman Ltd and RM Sotheby's, for the use of their pictures to illustrate this article.

“If you were rich in the 1970s, the Stutz Blackhawk was the car to flaunt your wealth”

I think that sentence should read “If you were rich in the 1970s, the Stutz Blackhawk was the car to flaunt your lack of taste” LOL